Sunni and Shi'i

When Muhammad died, Muslims faced the challenge of creating institutions to preserve the community. Muslims believe that the revelation was completed with the work of Muhammad, who is described as the seal of the prophets. The leaders after Muhammad were described only as khalifahs (caliphs), or successors to the Prophet, and not as prophets themselves. The first four caliphs were companions of the Prophet and their period of rule (632-661) is described by the majority of Muslims as the age of the Rightly Guided Caliphate. This was an era of expansion during which Muslims conquered the Sasanid (Persian) Empire and took control of the North African and Syrian territories of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. The Muslim community was transformed from a small city-state controlling much of the Arabian Peninsula into a major world empire extending from northwest Africa to central Asia.

This era ended with the first civil war (656-661), in which specific conflicts between particular interest groups provided the foundation for the broader political and theological divisions in the community and the Islamic tradition. The first two caliphs, Abu Bakr and Umar, had been successful in maintaining a sense of communal unity. But tensions within the community surfaced during the era of the third caliph, Uthman, who was from the Umayyad clan. Uthman was murdered in 656 by troops who mutinied over matters of pay and privileges, but the murder was the beginning of a major civil war.

The mutinous troops and others in Medina declared the new caliph to be Ali, a cousin of Muhammad who was an early convert and also the husband of Muhammad's daughter Fatimah (and, therefore, the father of Muhammad's only grandsons, Hasan and Husayn). According to Shi'i Muslim tradition, there were many people who believed that Muhammad had designated Ali as his successor. An Arabic term for faction or party is shi'ah, and the party or shi'ah of Ali emerged clearly during this first civil war. Ali's leadership was first challenged by a group including Aisha, the Prophet's most prominent wife and a daughter of the first caliph, Abu Bakr. Although Ali defeated this group militarily, it represented the tradition that became part of the mainstream majority, or Sunni, tradition in Islam, recognizing that all four of the first four caliphs were rightly guided and legitimate.

Ali faced a major military threat from the Umayyad clan, who demanded revenge for the murder of their kinsman, Uthman. The leader of the Umayyads was Muawiya, the governor of Syria. In a battle between the Umayyad army and the forces of Ali at Siffin in 657, Ali agreed to arbitration. As a result, a group of anti-Umayyad extremists withdrew from Ali's forces and became known as the Kharijites, or seceders, who demanded sinlessness as a quality of their leader and would recognize any pious Muslim as eligible to be the caliph. When Ali was murdered by a Kharijite in 661, most Muslims accepted Muawiya as caliph as a way of bringing an end to the intracommunal violence.

Many later divisions within the Muslim community were to be expressed in terms first articulated during this civil war. The mainstream, or Sunni, tradition reflects a combination of an emphasis on the consensus and piety of the community of the Prophet's companions, as reflected in the views of Aisha and her supporters, and the pragmatism of the Umayyad imperial administrators. The Sunni tradition always reflects the tension between the needs of state stability and the aspirations of a more egalitarian and pietistic religious vision. Shi'i Islam has its beginnings in the party of Ali and the argument that God always provides a special guide, or imam, for humans and that this guide has special characteristics, including being a descendant of the Prophet and having special divine guidance. Leadership and authority rest with this imamate and are not subject to human consensus or pragmatic reasons of state.

Makkah al-Mukarramah—"Makkah the Honored"—was the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad in 570. Within today's city, at the center of the Sacred Mosque is the focal point of Islamic prayer worldwide—the Ka'ba. The 15-meter-high (48'), roughly cubical structure was first built as a place for worship of the one God by Ibrahim (Abraham) and Isma'il (Ishmael), and it is thus a physical reminder of the links between Islam and the dawn of monotheism, between the Qur'an and previous revelations, and between the Prophet Muhammad and earlier Messengers of God. (Aramco World Magazine, January-February 1999; photo Peter Sanders). |

The Kharijites represent an extreme pietism that expects sinlessness from its leaders and asserts the right of the pious believer to declare others to be unbelievers. Over the centuries, explicitly Kharijite movements have declined in importance within the Muslim world, and by the late twentieth century were represented by small communities in the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa. The spirit of puritanical anarchism, however, although always a minority position within the Muslim community, has continued to provide a marginal but significant critique of existing conditions. Activist, sometimes militant, movements of puritanical renewal that exist throughout Islamic history are sometimes accused of being Kharijite in method if not in theology.

Another major period of civil conflict followed the death in 680 of the first Umayyad caliph, Muawiya. The Umayyad victory by 692 affirmed the pragmatic, consensus-oriented approach of the rising Sunni mainstream. Umayyad military power and the emerging pious elite's fear of anarchy resulted in the majoritarian compromise that is fundamental to Sunni views of society, community, and state. There is a tension between the pragmatic needs of soldiers and politicians and the moral aspirations of religious teachers. The Sunni majority usually accepted the necessary compromises, legitimized by the authority of the consensus of the community.

The main opposition to the structures of the new imperial community came from developing Shi'i traditions. Husayn, Ali's son, and a small group of his supporters were killed by an Umayyad army at Karbala in 680, and Husayn became a symbol of pious martyrdom in the path of God.

When the Umayyads were overthrown in the civil war of 744-750, the core of the revolutionary movement was Shi'ah. Piety-minded scholars, who were increasingly opposed to the worldly materialism of the Umayyads, joined the opposition. The organizers of the revolution were supporters of the Abbasids, the family of Abbas, an uncle of the Prophet, and when an Abbasid was proclaimed caliph following the defeat of the Umayyads, the supporters of the line of Ali remained in opposition. The new Abbasid caliphs reestablished the pragmatic compromise with the pious mainstream, and the Abbasid state succeeded as the new version of the Sunni caliphate.

Caliphs, Sultans, and the New Community

The world of Islam continued to expand, even during periods of civil war. By the mid-eighth century, Muslim conquests extended from the Iberian Peninsula to the inner Asian frontiers of China. The new Muslim state was, in many ways, the successor to the imperial systems of Persia and Rome, but the caliphates were clearly identified with Islam. The boundaries of the state and the Muslim community were basically the same, and the rulers, even when they were not known for piety, were still viewed by the majority as the successors to the Prophet.

It was the people of knowledge, or ulama, of the mainstream and not the caliphs who defined Islamic doctrine. Although there were state-appointed judges, Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) was defined by independent ulama. The Sunni majority came to accept four schools of legal thought--the Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, and Hanbali--as legitimate. By the eleventh century the ulama had also compiled authoritative collections of hadith, providing a standard for understanding the Sunnah of the Prophet. In this way, the Sunni tradition developed within the caliphal state but was not identical to it.

By the middle of the tenth century, the effective political and military power of the Abbasid caliphs had been greatly reduced. Power shifted to the military commanders who frequently took the title of sultan, meaning authority or power. The Abbasid caliphs continued to reside in Baghdad and provided formal recognition to sultans. Increasingly, military leadership was Turkish. Turks had come to the Middle East from Central Asia as slaves and mercenaries, but by the eleventh century there was a significant migration of Turkish peoples into the region. In 1055 Turks, under the leadership of the Seljuqs, took control of Baghdad and established a major sultanate in cooperation with the Abbasid caliphs. The new Seljuq sultanate represented a reorganization of Muslim institutions with great patronage for the ulama and establishment of the sultanate as the legitimate political system. This caliph-based sultanate system came to an end when the Mongols invaded the Middle East and conquered Baghdad in 1258.

In the era of the decline of the Sunni caliphate, Shi'i influence increased. During the eighth century Ja'far al-Sadiq, the sixth imam in the line of succession from Ali, provided the first fully comprehensive statement of Shi'i beliefs that became the basis for subsequent Shi'i mainstream groups. He provided opposition-ideology to the Sunni definition of the community but did not advocate revolution or virulent opposition to the Abbasids. The role of the imam was emphasized, and by the middle of the tenth century the moderate Shi'i mainstream accepted the imamate as spiritual and eschatological guide. This view defined a succession of twelve imams, the last of whom would enter a state of occultation and return as a messiah, or mahdi, in the future. The willingness to postpone expectations of a truly Islamic society until that return is an important part of Twelve-Imam (ithna ashari) Shi'ism. A minority maintained a more radical opposition, calling for messianic revolt, and identified with Ismail, a son of Sadiq who was not recognized by the Shi'i majority as being in the succession of imams. Ismaili Shi'ism provided the basis for the Fatimid movement in North Africa, which conquered Egypt in the tenth century and established a powerful Shi'i caliphate that lasted for more than two hundred years.

The fall of Baghdad to the Mongols did not mean the end of the sultanates. The military commanders continued to rule as sultans, even in the absence of caliphs, working with ulama and popular societal associations. This system of rule by military commanders without caliphs but identified as defenders and supporters of Islam became common in many parts of the Muslim world. The Mongol advance had been stopped by the Mamluk commanders of Egypt. Mamluks were legally slaves, and in the crisis of the thirteenth century, the commanders simply took control of the state and created a distinctive, self-perpetuating slave elite that ruled Egypt and much of Syria until the early sixteenth century.

In northern India Turkish slave-soldiers established the Delhi Sultanate, and in Anatolia remnants of the Seljuq state provided a basis for a number of Turkish military states, including the Ottomans, who gradually came to dominate the region. Even the Mongol commanders in the Middle East and Central Asia, often with the title of khan rather than sultan, converted to Islam and ruled sultanate-style states. In North Africa caliphal authority had been supplanted in the eleventh and twelfth centuries by first the Almoravids (Murabitun) and then the Almohads (Muwahhidun). Successor states in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia were more in the sultanate model.

Although the Muslim world was no longer politically unified, the era of the sultanates was a time of creativity and dynamism when the classical formulations of many aspects of Islamic faith and community were fully articulated. The schools of Islamic law were consolidated and supported by the rulers, and standard texts came to be used throughout the Muslim world.

The traditions of mystic piety, called Sufism in the Islamic world, were formulated in works of people like Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (1058-1111), who promoted acceptance of inner spirituality as an important part of Islamic life, and Muhyi al-Din Ibn al-Arabi (1165-1240), who extended Sufism with a more pantheistic outlook that became the heart of subsequent presentations of Muslim mysticism. More puritanical renewalism received a classic articulation in the works of Ahmad Ibn Taimiyya (1263-1328), who argued that rulers who did not strictly rule in accord with Islamic law should be considered infidels and opposed by jihad if necessary. He defined this position in opposition to the newly converted Mongol rulers of the early fourteenth century, but his works have been an inspiration to many later activist movements.

Spread of Islam

From the end of the effective power of the caliphs in the tenth century to the beginning of the sixteenth, the size of the Muslim world almost doubled. The vehicles for expansion were not conquering armies so much as traveling merchants and itinerant teachers. In Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa, in Central Asia, and in the many different societies in the Indian Ocean basin, a growing number of people came to be included within the world community of Islam.

Islamization usually involved an increasing familiarity with the basic texts and teachings of Islam and an awareness of being part of a larger community of believers. In contrast to early expansion in the Middle East, where monotheistic faiths like Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism were well established, much of this later growth was in areas where faith traditions were polytheistic or naturalistic. As Muslim teachers and merchants interacted with local rulers, they helped transform political systems that had been based on divine rule or rulers with special naturalistic powers and obligations. In the courts of Java and West Africa, as well as among the shamans of Central Asia, the coming of Islam changed both political structures and popular faith. Often this involved incorporating local beliefs and customs that created distinctive local Muslim communities within the intercontinental community of believers.

Devotional teachers were also important in the world of the sultanates. The spiritual life associated with Sufism came to be institutionalized in organizations identified by the devotional paths, or tariqahs, of famous Sufis. One of the earliest of these was the Qadiriyya Tariqah, tracing itself back to Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani in twelfth-century Baghdad. Because they were tied to popular piety, tariqahs often served to meld local practices with Islamic ideas, and the brotherhoods were a major force in the gradual Islamization of many societies.

By the end of the fifteenth century the Muslim world was very different from what it had been at the height of Abbasid power. No single state could be identified, even in theory, with the whole community of believers. Although the society and culture of the early caliphates were primarily Middle Eastern, the Islamic world of the fifteenth century brought together peoples from different civilizations and nonurban societies. Islam was no longer a faith identified with a particular world region; it had become more universal and cosmopolitan in its articulation and in the nature of the community of believers.

Contributions of the Islamic Empire

One of the greatest contributions was the Arabic language,

the predominant language of the area.

The Koran was written in Arabic as well.

The Arabs introduced stock-raising and new crops such as

sugarcane, cotton, rice, and fruits to

Trade flourished, and cities grew.

Ideas from throughout the world were brought together in intellectual

centers. Science and mathematics

discoveries were made in trigonometry, geometry, and astronomy.

Hospitals were established throughout the empire, and extensive medical

achievements were made.

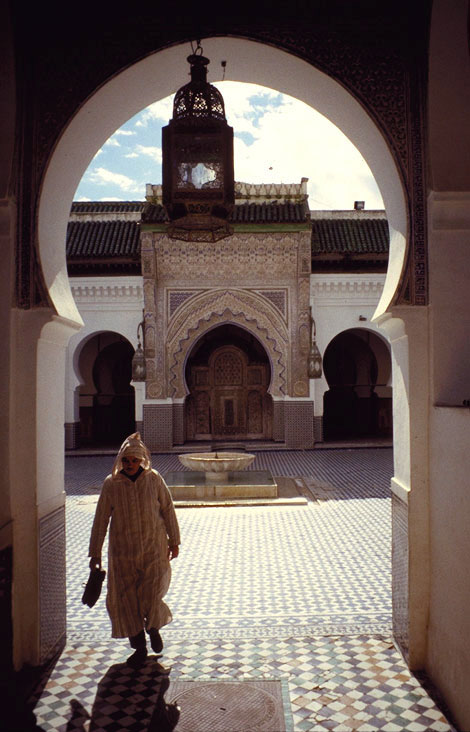

In art and humanities the Moslems created exquisite mosaics

as well as outstanding mosques.

Downfall of the Islamic Empire

The continuous problem of the succession of the caliphate

became more and more serious as rival dynasties claimed control.

Internal clashes such as the break between social classes, between the

northern and southern territories, and within the Moslem religion tore the

empire apart. The outer

territories of the empire including