Islam

Religion and Philosophy

Islam is

Christianity’s only rival as a world religion in

the vigour and range of its geographical spread.

It springs ultimately from the same roots as Christianity, the tribal

cultures of the Semitic peoples of the

The Five Pillars

The religious

duties and beliefs of a Moslem are known as the Five Pillars of Islam. The

word Islam means submission to the will of God.

Despite a

rich diversity in Islamic practice, there are five simple required observances

prescribed in the Quran that all practicing Muslims accept

and follow. These "Pillars of Islam" represent the core and common

denominator that unites all Muslims and distinguishes Islam from other

religions. Following the Pillars of Islam requires dedication of your mind,

feelings, body, time, energies, and possessions. Meeting the obligations

required by the Pillars reinforces an ongoing presence of God in Muslims'

lives and reminds them of their membership in a single worldwide community of

believers.

1. The first pillar is called the Declaration of Faith . A Muslim is

one who bears witness, who testifies that "there is no god but God [Allah] and

Muhammad is the messenger of God." This declaration is known as the

shahada (witness,

testimony) . Allah is the Arabic name for God, just as Yahweh is the

Hebrew name for God used in the Old Testament. To become a Muslim, one need

only make this simple proclamation.

The first part of this proclamation affirms Islam's absolute monotheism, the

uncompromising belief in the oneness or unity of God, as well as the doctrine

that association of anything else with God is idolatry and the one

unforgivable sin. As we see in Quran 4:48 :

"God does not forgive anyone for associating something with Him, while He does forgive whomever He wishes to for anything else. Anyone who gives God associates [partners] has invented an awful sin."

This helps us

to understand the Islamic belief that its revelation is intended to correct

such departures from the "straight path" as the Christian concept of the

Trinity and veneration of the Virgin Mary in Catholicism.

The second part of the confession of faith asserts that Muhammad is not only a

prophet but also a messenger of God, a higher role also played by Moses and

Jesus before him. For Muslims, Muhammad is the vehicle for the last and final

revelation. In accepting Muhammad as the "seal of the prophets," they believe

that his prophecy confirms and completes all of the revealed messages,

beginning with Adam's. In addition, somewhat like Jesus Christ, Muhammad

serves as the preeminent role model through his life example. The believer's

effort to follow Muhammad's example reflects the emphasis of Islam on practice

and action. In this regard Islam is more like Judaism, with its emphasis upon

the law, than Christianity, which gives greater importance to the importance

of doctrines or dogma. This practical orientation of Islam is reflected in the

remaining four Pillars of Islam.

2. The second Pillar of Islam is Prayer ( salat

). Muslims pray (or, perhaps more correctly, worship) five times throughout

the day: at daybreak, noon, midafternoon, sunset, and evening. Although the

times for prayer and the ritual actions were not specified in the Quran,

Muhammad established them.

In many Muslim countries, reminders to pray, or "calls to prayer" echo out

across the rooftops. Aided by a megaphone, from high atop a mosque's minaret,

the muezzin calls out:

God is most great [ Allahu Akbar ], God is most great, God is most great, God is most great, I witness that there is no god but God [ Allah ]; I witness that there is no god but God. I witness that Muhammad is the messenger of God. I witness that Muhammad is the messenger of God. Come to prayer; come to prayer! Come to prosperity; come to prosperity! God is most great. God is most great. There is no god but God.

These reminders throughout the day help to keep believers mindful of God in

the midst of everyday concerns about work and family with all their

attractions and distractions. It strengthens the conscience, reaffirms total

dependence on God, and puts worldly concerns within the perspective of death,

the last judgment, and the afterlife.

The prayers consist of recitations from the Quran in Arabic and glorification

of God. These are accompanied by a sequence of movements: standing, bowing,

kneeling, touching the ground with one's forehead, and sitting. Both the

recitations and accompanying movements express submission, humility, and

adoration of God. Muslims can pray in any clean environment, alone or

together, in a mosque or at home, at work or on the road, indoors or out. It

is considered preferable and more meritorious to pray with others, if

possible, as one body united in the worship of God, demonstrating discipline,

brotherhood, equality, and solidarity.

As they prepare to pray, Muslims face Mecca, the holy city that houses the

Kaaba (the house of God believed to have been built by Abraham and his son

Ismail). Each act of worship begins with the declaration that "God is most

great" (" Allahu Akbar ") and is followed by fixed

prayers that include the opening verse of the Quran.

At the end of the prayer, the shahada (declaration

of faith) is again recited, and the "'peace greeting" - " Peace be upon all of

you and the mercy and blessings of God" is repeated twice.

3. The third Pillar of Islam is called the Zakat,

which means "purification." Like prayer, which is both an individual and

communal responsibility, zakat expresses a

Muslim's worship of and thanksgiving to God by supporting the poor. It

requires an annual contribution of 2.5 percent of an individual's wealth and

assets, not merely a percentage of annual income. In Islam, the true owner of

things is not man but God. People are given their wealth as a trust from God.

Therefore, zakat is not viewed as "charity"; it is an obligation for those who

have received their wealth from God to respond to the needs of less fortunate

members of the community. The Quran (9:60) as

well as Islamic law stipulates that alms are to be used to support the poor,

orphans, and widows, to free slaves and debtors, and to support those working

in the "cause of God" (e.g., construction of mosques, religious schools, and

hospitals, etc.). Zakat, developed fourteen hundred years ago, functions as a

form of social security in a Muslim society. In Shii Islam, in addition to the

zakat, which is not limited to 2.5 percent,

believers pay a religious tax ( khums ) on their

income to a religious leader. This is used to support the poor and needy.

4. The fourth Pillar of Islam, the Fast of Ramadan, occurs once each

year during the month of Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar and

the month in which the first revelation of the Quran came to Muhammad. During

this month-long fast, Muslims whose health permits must abstain from dawn to

sunset from food, drink, and sexual activity. Fasting is a practice common to

many religions, sometimes undertaken as penance, sometimes to free us from

undue focus on physical needs and appetites. In Islam the discipline of the

Ramadan fast is intended to stimulate reflection on human frailty and

dependence upon God, focus on spiritual goals and values, and identification

with and response to the less fortunate.

At dusk the fast is broken with a light meal popularly referred to as

breakfast. Families and friends share a special late evening meal together,

often including special foods and sweets served only at this time of the year.

Many go to the mosque for the evening prayer, followed by special prayers

recited only during Ramadan. Some will recite the entire Quran (one-thirtieth

each night of the month) as a special act of piety, and public recitations of

the Quran or Sufi chanting can be heard throughout the evening. Families rise

before sunrise to take their first meal of the day, which must sustain them

until sunset.

Near the end of Ramadan (the twenty-seventh day) Muslims commemorate the

"Night of Power" when Muhammad first received God's revelation. The month of

Ramadan ends with one of the two major Islamic celebrations, the Feast of the

Breaking of the Fast, called Eid al-Fitr, which

resembles Christmas in its spirit of joyfulness, special celebrations, and

gift giving.

5. The fifth Pillar is the Pilgrimage or Hajj

to

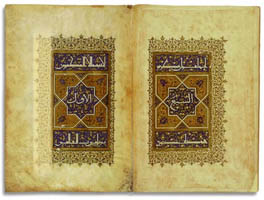

The Quran

Mohammed’s followers wrote down his prophecies after his death, creating the Quran. Its essence was the assertion that no God was to be worshipped but Allah; Islam was uncompromisingly monotheistic. One objection Moslems had to Christianity was that they believed it to be polytheistic, because it gave as much importance to Jesus and the Holy Spirit as to God the Father.

For Muslims, or followers of Islam, the Quran is the actual Word of God revealed through the archangel Gabriel to the Prophet of Islam during the twenty-three-year period of his prophetic mission. It was revealed in the Arabic language as a sonoral revelation which the Prophet repeated to his companions. Arabic became therefore the language of Islam even for non-Arab Muslims. Under the direction of the Prophet, the verses and chapters were organized in the order known to Muslims to this day. There is only one text of the Quran accepted by all schools of Islamic thought and there are no variants. The Quran is the central sacred reality of Islam. The sound of the Quran is the first and last sound that a Muslim hears in this life. As the direct Word of God and the embodiment of God's Will, the Quran is considered as the guide par excellence for the life of Muslims. It is the source of all Islamic doctrines and ethics. Both the intellectual aspects of Islam and Islamic Law have their source in the Quran. Perhaps there is no book revered by any human collectivity as much as the Quran is revered by Muslims. Essentially a religion of the book, Islam sees all authentic religions as being associated with a scripture. That is why Muslims call Christians and Jews the "people of the book". Throughout all its chapters and verses, the Quran emphasizes the significance of knowledge and encourages Muslims to learn and to acquire knowledge not only of God's laws and religious injunctions, but also of the world of nature. The Quran refers, in a language rich in its varied terminology, to the importance of seeing, contemplating, and reasoning about the world of creation and its diverse phenomena. It places the gaining of knowledge as the highest religious activity, one that is most pleasing in God's eyes. That is why wherever the message of the Quran was accepted and understood, the quest for knowledge flourished.

Despite the

recent example of the Taliban in Afghanistan and sporadic conflicts between

Muslims and Christians in Sudan, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Indonesia,

theologically and historically Islam has a long record of tolerance.

The Quran clearly and strongly states that "there is to be no compulsion in

religion" (2:256), and that God has created not

one but many nations and peoples. Many passages underscore the diversity of

humankind. The Quran teaches that God deliberately created a world of

diversity (49:13) :

"O humankind, We have created you male and female and made you nations and tribes, so that you might come to know one another."

Muslims, like

Christians and Jews before them, believe that they have been called to a

special covenant relationship with God, constituting a community of believers

intended to serve as an example to other nations

(2:143) in establishing a just social order

(3:110) .

Moreover, Muslims regard Jews and Christians as "People of the Book," people

who have also received a revelation and a scripture from God (the Torah for

Jews and the Gospels for Christians). The Quran and Islam recognize that

followers of the three great Abrahamic religions, the children of Abraham,

share a common belief in the one God, in biblical prophets such as Moses and

Jesus, in human accountability, and in a Final Judgment followed by eternal

reward or punishment. All share the common hope and promise of eternal reward:

"Surely the believers and the Jews, Christians and Sabians [Middle East groups traditionally recognized by Islam as having a monotheistic orientation], whoever believes in God and the Last Day, and whoever does right, shall have his reward with his Lord and will neither have fear nor regret"

(2:62)

.

Historically, while the early expansion and conquests spread Islamic rule,

Muslims did not try to imposetheir religion on others or force them to

convert. As "People of the Book," Jews and Christians were regarded as

protected people ( dhimmi ), who were permitted to

retain and practice their religions, be led by their own religious leaders,

and be guided by their own religious laws and customs. For this protection,

they paid a poll or head tax ( jizya ). While by

modern standards this treatment amounted to second-class citizenship in

premodern times, it was very advanced. No such tolerance existed in

Christendom, where Jews, Muslims, and other Christians (those who did not

accept the authority of the pope) were subjected to forced conversion,

persecution, or expulsion. Although the Islamic ideal was not followed

everywhere and at all times, it existed and flourished in many contexts.

In recent years, religious intolerance has become a major issue in self-styled

Islamic governments in Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan under the Taliban, Iran, and

Sudan, as well as in the actions of religious extremist organizations from

Egypt's Islamic Jihad to Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda who have been intolerant

toward not only non-Muslims but also other Muslims who do not accept their

version of "true Islam." The situation is exacerbated in some countries where

Muslims have clashed with Christians (Nigeria, the Philippines, and

Indonesia), Hindus (India and Kashmir), and Jews (Israel). These

confrontations have sometimes been initiated by the Muslim community and

sometimes by the Christian. In some cases it becomes difficult to distinguish

whether conflicts are driven primarily by politics and economics or by

religion. Finally, more secular governments in Egypt, Tunisia, Turkey, Syria,

and elsewhere have often have proven to be intolerant of mainstream Islamic

organizations or parties that offer an alternative vision of society or are

critical of government policies.

From Egypt to Indonesia and Europe to America, many Muslims today work to

reexamine their faith in the light of the changing realities of their

societies and their lives, developing new approaches to diversity and

pluralism. Like Jews and Christians before them, they seek to reinterpret the

sources of their faith to produce new religious understandings that speak to

religious pluralism in the modern world. The need to redefine traditional

notions of pluralism and tolerance is driven by the fact that in countries

such as Egypt, Lebanon, Pakistan, India, Nigeria, Malaysia, and Indonesia,

Muslims live in multireligious societies, and also by new demographic

realities. Never before have so many Muslim minority communities existed

across the world, in particular in America and Europe. The specter of living

as a permanent minority community in non-Muslim countries has heightened the

need to address and redefine questions of pluralism and tolerance. Like Roman

Catholicism in the 1960s, whose official acceptance of pluralism at the Second

Vatican Council was strongly influenced by American Catholics' experience as a

minority, Muslim communities in America and Europe are now struggling with

their questions of identity and assimilation.

Reformers emphasize that diversity and pluralism are integral to the message

of the Quran, which teaches that God created a world composed of different

nations, ethnicities, tribes, and languages:

"To each of you We have given a law and a way and a pattern of life. If God had pleased He could surely have made you one people [professing one faith]. But He wished to try and test you by that which He gave you. So try to excel in good deeds. To Him will you all return in the end, when He will tell you how you differed"

(5:48)

. Many point to the example of the Prophet and his community at Medina. The

Constitution of Medina accepted the coexistence of Muslims, Jews, and

Christians. Muhammad discussed and debated with, and granted freedom of

religious thought and practice to, the Jews and Christians, setting a

precedent for peaceful and cooperative interreligious relations. Many

challenge the exclusivist religious claims and intolerance of Islamic groups

who believe that they alone possess the "true" interpretation of Islam and

attempt to impose it on other Muslims and non-Muslims alike. In many ways,

Islam today is at a crossroads as Muslims, mainstream and extremist,

conservative and progressive, struggle to balance the affirmation of the truth

of their faith with the cultivation of a pluralism and tolerance rooted in

mutual respect and understanding.

The Two Branches of Islam

As a world

religion, Islam is practiced in diverse cultures in Africa, the Middle East,

Asia, Europe, and America. Differences in religious and cultural practices are

therefore wide-ranging. Although there are no denominations in Islam such as

exist in the Christian faith (Roman Catholic, Methodist, Episcopalian,

Lutheran, etc.), like all faiths, Islam has developed divisions, sects, and

schools of thought over various issues. While all Muslims share certain

beliefs and practices, such as belief in God, the Quran, Muhammad, and the

Five Pillars of Islam, divisions have arisen over questions of political and

religious leadership, theology, interpretations of Islamic law, and responses

to modernity and the West.

The division of opinion about political and religious leadership after the

death of Muhammad led to the division of Muslims into two major branches -

Sunnis (85 percent of all Muslims) and Shiis (15 percent). (See next

question.) In addition, a small but significant radical minority known as the

Kharijites should be mentioned. Although they have never won large numbers of

followers, their unique theological position has continued to influence

political and religious debate up to the present day.

Sunni Muslims believe that because Muhammad did not designate a successor, the

best or most qualified person should be either selected or elected as leader (

caliph ). Because the Quran declared Muhammad to

be the last of the prophets, this caliph was to

succeed Muhammad as the political leader only. Sunnis believe that the

caliph should serve as the protector of the faith,

but he does not enjoy any special religious status or inspiration.

Shiis, by contrast, believe that succession to the leadership of the Muslim

community should be hereditary, passed down to Muhammad's male descendants

(descended from Muhammad's daughter Fatima and her husband Ali), who are known

as Imams and who are to serve as both religious and political leaders. Shiis

believe that the Imam is religiously inspired, sinless, and the interpreter of

God's will as contained in Islamic law, but not a prophet. Shiis consider the

sayings, deeds, and writings of their Imams to be authoritative religious

texts, in addition to the Quran and Sunnah. Shiis further split into three

main divisions as a result of disagreement over the number of Imams who

succeeded Muhammad. [...]

The Kharijites (from kharaja, to go out or exit)

began as followers of the caliph Ali, but they broke away from him because

they believed him to be guilty of compromising God's will when he agreed to

arbitrate rather than continue to fight a long, drawn-out war against a

rebellious general. After separating from Ali (whom they eventually

assassinated), the Kharijites established a separate community designed to be

a "true" charismatic society strictly following the Quran and Sunnah of the

Prophet Muhammad. The Kharijite world was separated neatly into believers and

nonbelievers, Muslims (followers of God) and non-Muslims (enemies of God).

These enemies could include other Muslims who did not accept the

uncompromising Kharijite point of view. Sinners were to be excommunicated and

were subject to death unless they repented. Therefore, a

caliph or ruler could only hold office as long as he was sinless. If he

fell from this state, he was outside the protection of law and must be deposed

or killed. This mentality influenced the famous medieval theologian and legal

scholar Ibn Taymiyyah and has been replicated in modern times by Islamic

Jihad, the group that assassinated Egypt's President Anwar Sadat, as well as

by Osama bin Laden and other extremists who call for the overthrow of

"un-Islamic" Muslim rulers.

Differences of opinion about political and religious leadership have led

Sunnis and Shiis to hold very different visions of sacred history. Sunnis

experienced a glorious and victorious history under the Four Rightly Guided

Caliphs and the expansion and development of Muslim empires under the Umayyad

and Abbasid dynasties. Sunnis can thus claim a golden age in which they were a

great world power and civilization, which they see as evidence of God's

guidance and the truth of the mission of Islam. Shiis, on the other hand,

struggled unsuccessfully during the same time period against Sunni rule in the

attempt to restore the imamate they believed God had appointed. Therefore,

Shiis see in this time period the illegitimate usurpation of power by the

Sunnis at the expense of creating a just society. Shii historical memory

emphasizes the suffering and oppression of the righteous, the need to protest

against injustice, and the requirement that Muslims be willing to sacrifice

everything, including their lives, in the struggle with the overwhelming

forces of evil (Satan) in order to restore God's righteous rule.

Divisions of opinion also exist with respect to theological questions. One

historical example is the question of whether a ruler judged guilty of a grave

(mortal) sin should still be considered legitimate or should be overthrown and

killed. Most Sunni theologians and jurists taught that the preservation of

social order was more important than the character of the ruler. They also

taught that only God on Judgment Day is capable of judging sinners and

determining whether or not they are faithful and deserving of Paradise.

Therefore, they concluded that the ruler should remain in power since he could

not be judged by his subjects. Ibn Taymiyya was the one major theologian and

jurist who made an exception to this position and taught instead that a ruler

should and must be overthrown.

Ibn Taymiyya's ire was directed at the Mongols. Despite their conversion to

Islam, they continued to follow the Yasa code of laws of Genghis Khan instead

of the Islamic law, Shariah . For Ibn Taymiyya

this made them no better than the polytheists of the pre-Islamic period. He

issued a fatwa (formal legal opinion) that labeled

them as unbelievers ( kafirs ) who were thus

excommunicated ( takfir ). This

fatwa established a precedent: despite their claim

to be Muslims, their failure to implement Shariah rendered the Mongols

apostates and hence the lawful object of jihad .

Muslim citizens thus had the right, indeed duty, to revolt against them, to

wage jihad . Ibn Taymiyya's opinions remain

relevant today because they have inspired the militancy and religious

worldview of organizations like Osama bin Laden's al-Qaeda network.

Other examples of divisions over theological questions include arguments over

whether the Quran was created or uncreated and whether it should be

interpreted literally or metaphorically and allegorically. Historically,

Muslims have also debated the question of free will versus predestination.

That is, are human beings truly free to choose their own actions or are all

actions predetermined by an omniscient God? What are the implications of such

beliefs upon human responsibility and justice?

Islamic law provides one of the clearest and most important examples of

diversity of opinions. Islamic law developed in response to the concrete

realities of daily life. Since the heart of Islam and being a Muslim is

submission to God's will, the primary question for believers was "What should

I do and how?" During the Umayyad Empire (661-750), rulers set up a

rudimentary legal system based upon the Quran, the Sunnah, and local customs

and traditions. However, many pious Muslims became concerned about the

influence of rulers on the development of the law. They wanted to anchor

Islamic law more firmly to its revealed sources and make it less vulnerable to

manipulation by rulers and their appointed judges.

Over the next two centuries, Muslims in the major cities of Medina, Mecca,

Kufa, Basra, and Damascus sought to discover and delineate God's will and law

through the science of jurisprudence. Although each city produced a

distinctive interpretation of the law, all cities shared a general legal

tradition. The earliest scholars of Islamic law were neither lawyers nor

judges nor students of a specific university. They were men who combined

professions such as trade with the study of Islamic texts. These loosely

connected scholars tended to be gathered around or associated with major

personalities. Their schools of thought came to be referred to as law schools.

While many law schools existed, only a few endured and were recognized as

authoritative. Today, there are four major Sunni law schools (Hanafi, Hanbali,

Maliki, and Shafii) and two major Shii schools (Jafari and Zaydis). The Hanafi

came to predominate in the Arab world and South Asia; the Maliki in North,

Central, and West Africa; the Shafii in East Africa and Southeast Asia; and

the Hanbali in Saudi Arabia. Muslims are free to follow any law school but

usually select the one that predominates in the area in which they are born or

live.

Perhaps nowhere are the differences in Islam more visible than in the

responses to modernity. Since the nineteenth century, Muslims have struggled

with the relationship of their religious tradition developed in premodern

times to the new demands (religious, political, economic, and social) of the

modern world. The issues are not only about Islam's accommodation to change

but also about the relationship of Islam to the West, since much of modern

change is associated with Western ideas, institutions, and values. Muslim

responses to issues of reform and modernization have spanned the spectrum from

secularists and Islamic modernists to religious conservatives or

traditionalists, "fundamentalists," and Islamic reformists.

Modern secularists are Western oriented and advocate a separation between

religion and the rest of society, including politics. They believe that

religion is and should be strictly a private matter. Islamic modernists

believe that Islam and modernity, particularly science and technology, are

compatible, so that Islam should inform public life without necessarily

dominating it. The other groups are more "Islamically" oriented but have

different opinions as to the role Islam should play in public life.

Conservatives, or traditionalists, emphasize the authority of the past and

tend to call for a reimplementation of Islamic laws and norms as they existed

in that past. "Fundamentalists" emphasize going back to the earliest period

and teachings of Islam, believing that the Islamic tradition needs to be

purified of popular, cultural, and Western beliefs and practices that have

"corrupted" Islam. However, the term fundamentalist is applied to such a broad

spectrum of Islamic movements and actors that, in the end, it includes both

those who simply want to reintroduce or restore their pure and puritanical

vision of a romanticized past and others who advocate modern reforms that are

rooted in Islamic principles and values. There are a significant number of

Islamic reformers, intellectuals, and religious leaders who also emphasize the

critical need for an Islamic reformation, a wide-ranging program of

reinterpretation ( ijtihad ) and reform urging

fresh approaches to Quranic interpretation as well as to issues of gender,

human rights, democratization, and legal reform.