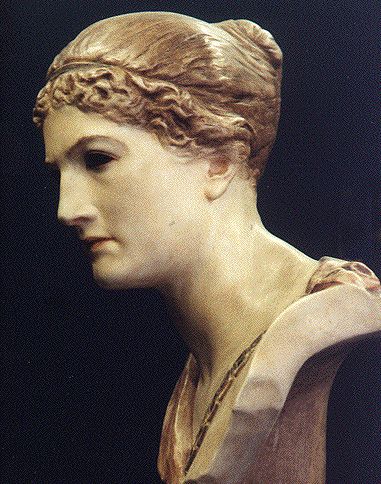

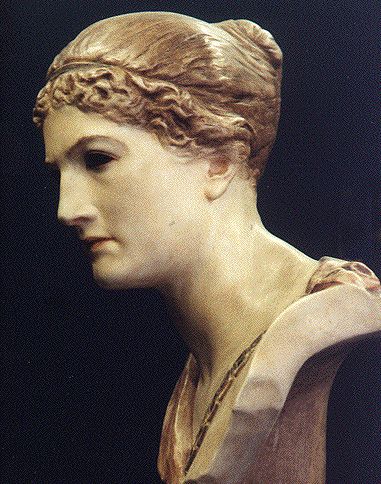

Laoco÷n and Cassandra were two people who tried to warn the Trojans against the acceptance of the wooden horse and both suffered in very different ways. Laoco÷n was destroyed by the gods, but Cassandra's suffering was much more subtle. We'll tell her story first.

Cassandra was a virgin priestess loyal to the goddess Athena. She was apparently very beautiful and adored by the god Apollo. The smitten god gave the cherished Cassandra the gift of prophecy, being able to have clear visions of future events. Cassandra promised her love to Apollo and then broke her promise out of piety to Athena. Apollo then became offended with her. Although he could not take back his gift, as divine favors once bestowed might not be revoked, Apollo condemned Cassandra to a misery of her own- he made it so no one believed her prophecies.

It is in such a situation that Cassandra finds herself when the wooden horse is brought to the walls of Troy. She has a clear vision of what will happen when the horse is accepted. Virgil relates the story thus:

. . .mad with zeal and blinded with our fate

We haul along the horse in solemn state;

Then place the dire portent within the tow'r.

Cassandra cried, and cursed the unhappy hour;

Foretold our fate; but by the god's decree,

All heard, and none believed the prophecy.

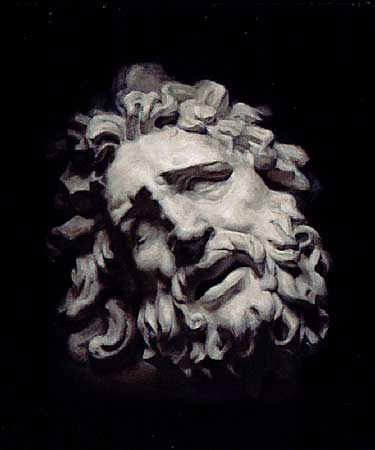

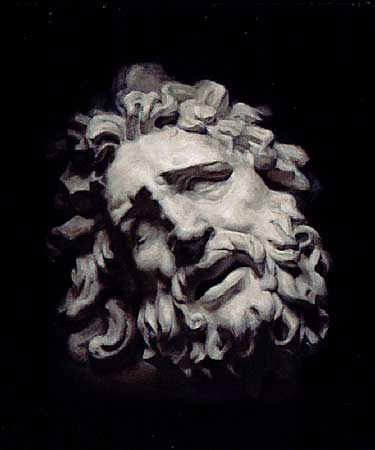

Laoco÷n suffered a much more painful fate for trying to warn his fellow citizens. He trooped out of the city with a group of men to support him and they advised strongly against taking in the horse. Virgil relates part of his speech:

'O wretched countrymen! what fury reigns?

What more than madness has possess'd your brains?

Think you the Grecians from your coasts are gone?

And are Ulysses' arts no better known?

This hollow fabric either must inclose,

Within its blind recess, our secret foes;

Or 't is an engine rais'd above the town,

T' o'erlook the walls, and then to batter down.

Somewhat is sure design'd, by fraud or force:

Trust not their presents, nor admit the horse.'

To conclude, he hurled his spear at the horse and, even though the shuffling and moaning of soldiers could be heard inside, the people refused to listen, so excited were they at the prospect of the war's end. Virgil's account, as well as the accounts of others, attribute the spurning of Laoco÷n by his city to the will of the gods. The gods had declared that Troy be destroyed and so it would be, regardless of Laoco÷n's pleading.

The wild god's of Greece were not content simply having Laoco÷n ignored. They encouraged the people by brutally killing Laoco÷n and his family. Virgil describes this horrific scene:

Laocoon, Neptune's priest by lot that year,

With solemn pomp then sacrific'd a steer;

When, dreadful to behold, from sea we spied

Two serpents, rank'd abreast, the seas divide,

And smoothly sweep along the swelling tide.

Their flaming crests above the waves they show;

Their bellies seem to burn the seas below;

Their speckled tails advance to steer their course,

And on the sounding shore the flying billows force.

And now the strand, and now the plain they held;

Their ardent eyes with bloody streaks were fill'd;

Their nimble tongues they brandish'd as they came,

And lick'd their hissing jaws, that sputter'd flame.

We fled amaz'd; their destin'd way they take,

And to Laocoon and his children make;

And first around the tender boys they wind,

Then with their sharpen'd fangs their limbs and bodies grind.

The wretched father, running to their aid

With pious haste, but vain, they next invade;

Twice round his waist their winding volumes roll'd;

And twice about his gasping throat they fold.

The priest thus doubly chok'd, their crests divide,

And tow'ring o'er his head in triumph ride.

With both his hands he labors at the knots;

His holy fillets the blue venom blots;

His roaring fills the flitting air around.